You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

MLB

- Thread starter blackfoot NAP

- Start date

blackfoot NAP

King Of Bling

Source: Marlins and Brandon Kintzler agree to 1-year, $3 million deal

Kintzler, 35, is coming off one of the best years of his career, compiling a 2.68 ERA and 1.018 WHIP with the Chicago Cubs. The former All-Star closer with the Minnesota Twins could regain his ninth-inning role with the Marlins, who feature a young team.

Source: Ryan Zimmerman agrees to 1-year deal with Nationals

He was the first player drafted by the Nationals in 2005 after the club moved from Montreal to Washington, and he has played in every one of their 15 seasons. He holds franchise career records for hits, doubles, total bases, homers and RBI.

.

Kintzler, 35, is coming off one of the best years of his career, compiling a 2.68 ERA and 1.018 WHIP with the Chicago Cubs. The former All-Star closer with the Minnesota Twins could regain his ninth-inning role with the Marlins, who feature a young team.

Source: Ryan Zimmerman agrees to 1-year deal with Nationals

He was the first player drafted by the Nationals in 2005 after the club moved from Montreal to Washington, and he has played in every one of their 15 seasons. He holds franchise career records for hits, doubles, total bases, homers and RBI.

.

blackfoot NAP

King Of Bling

Pirates agree with left-handers Derek Holland and Robbie Erlin to minor-league deals

The 33-year-old Holland is 78-78 with a 4.54 ERA in 11 seasons, including eight with the Texas Rangers. Holland split time between the San Francisco Giants and the Chicago Cubs last year, going 2-5 with a 6.08 ERA. Erlin, 29, is 13-20 with a 4.57 ERA in 106 appearances with the San Diego Padres.

Matt Adams agrees to minor league deal with Mets

The 31-year-old is primarily a first baseman but also has played the outfield. He batted .226 with 20 homers and 56 RBIs in 333 plate appearances last year for the World Series champion Washington Nationals, hitting 12 of his homers in June and July.

.

The 33-year-old Holland is 78-78 with a 4.54 ERA in 11 seasons, including eight with the Texas Rangers. Holland split time between the San Francisco Giants and the Chicago Cubs last year, going 2-5 with a 6.08 ERA. Erlin, 29, is 13-20 with a 4.57 ERA in 106 appearances with the San Diego Padres.

Matt Adams agrees to minor league deal with Mets

The 31-year-old is primarily a first baseman but also has played the outfield. He batted .226 with 20 homers and 56 RBIs in 333 plate appearances last year for the World Series champion Washington Nationals, hitting 12 of his homers in June and July.

.

blackfoot NAP

King Of Bling

Source: White Sox reach deal with Cuban RHP Norge Carlos Vera

Vera, 18, pitched for Cuba's national team in June against the New Jersey Jackals of the independent Can-Am League and defected after that start, before he was set to pitch against the collegiate Team USA.

Rangers sign former closer Cody Allen to minor league deal

Allen is Cleveland's career leader in saves (149) and in appearances (456) and strikeouts (564) by a reliever.

.

Vera, 18, pitched for Cuba's national team in June against the New Jersey Jackals of the independent Can-Am League and defected after that start, before he was set to pitch against the collegiate Team USA.

Rangers sign former closer Cody Allen to minor league deal

Allen is Cleveland's career leader in saves (149) and in appearances (456) and strikeouts (564) by a reliever.

.

blackfoot NAP

King Of Bling

MLB rule changes for 2020: What you need to know

Major League Baseball will roll out several rule changes for the 2020 season, the most dramatic being the three-batter minimum for pitchers. The new three-batter rule, which requires pitchers to face at least three batters or finish a half inning, will have the biggest impact on game action, but the other changes should have a notable impact as well.

.

Major League Baseball will roll out several rule changes for the 2020 season, the most dramatic being the three-batter minimum for pitchers. The new three-batter rule, which requires pitchers to face at least three batters or finish a half inning, will have the biggest impact on game action, but the other changes should have a notable impact as well.

.

C-40

NEW AGE POSTING

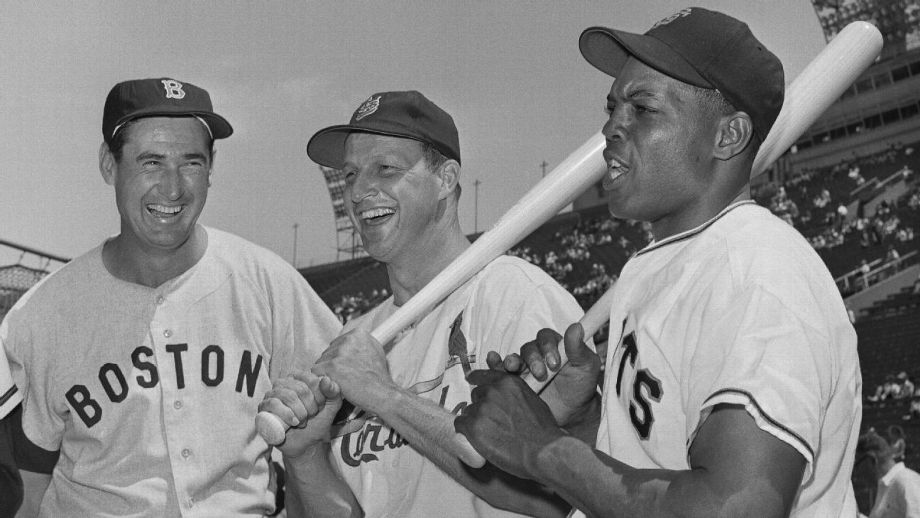

Lawmakers push for Curt Flood's enshrinement in Hall of Fame

Curt Flood's widow has a simple explanation for why her late husband, who is revered by players for sacrificing his career to advocat e for free agency, has not been enshrined in baseball's Hall of Fame."I think the holdup is that he got on a lot of people's nerves," Judy Pace Flood said.Flood has some powerful advocates on his side. Members of Congress sent a letter to the Hall of Fame on Thursday asking that Flood be elected in December by the next Golden Days committee. The recognition would coincide with the 50-year anniversary of Flood's defiant letter to baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn in which he wrote, "I do not feel that I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes."

For Complete Story, Click Here.

Curt Flood's widow has a simple explanation for why her late husband, who is revered by players for sacrificing his career to advocat e for free agency, has not been enshrined in baseball's Hall of Fame."I think the holdup is that he got on a lot of people's nerves," Judy Pace Flood said.Flood has some powerful advocates on his side. Members of Congress sent a letter to the Hall of Fame on Thursday asking that Flood be elected in December by the next Golden Days committee. The recognition would coincide with the 50-year anniversary of Flood's defiant letter to baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn in which he wrote, "I do not feel that I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes."

For Complete Story, Click Here.

blackfoot NAP

King Of Bling

Everything you need to know about MLB's sign-stealing scandal

Major League Baseball's sign-stealing saga is the biggest scandal in the sport since the steroid era.

Complete 2020 MLB spring training schedule

.

Major League Baseball's sign-stealing saga is the biggest scandal in the sport since the steroid era.

Complete 2020 MLB spring training schedule

.

Charlemagne

Holy Roman Emperor

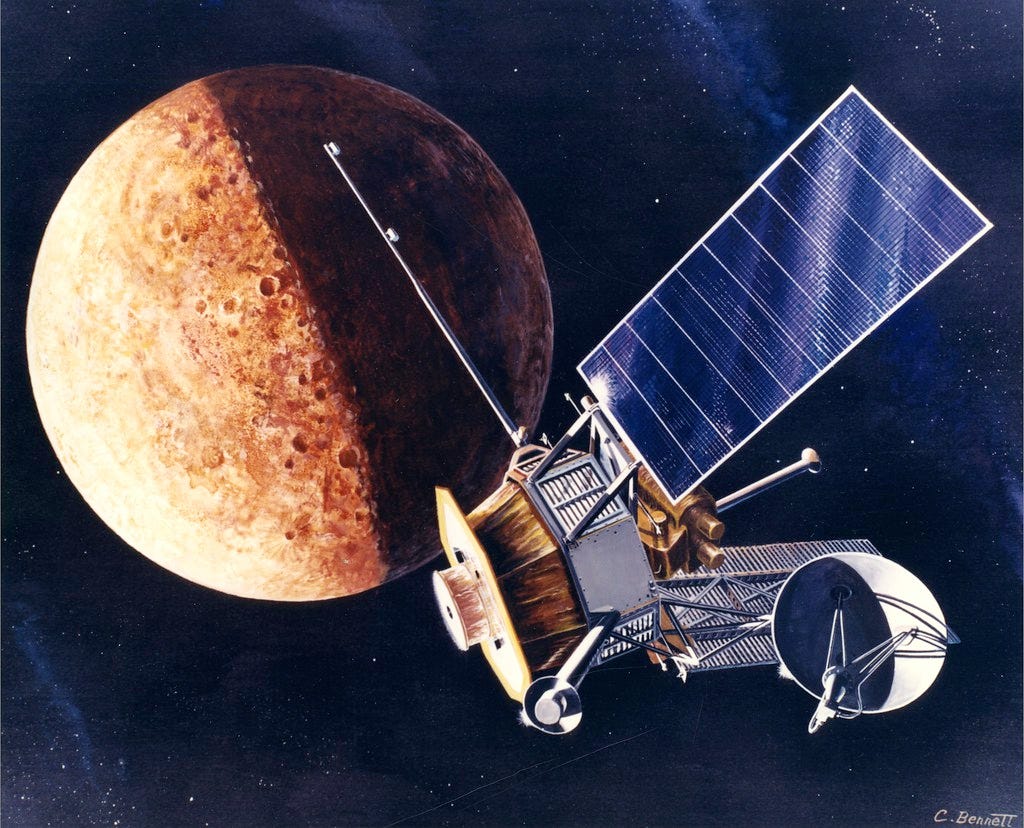

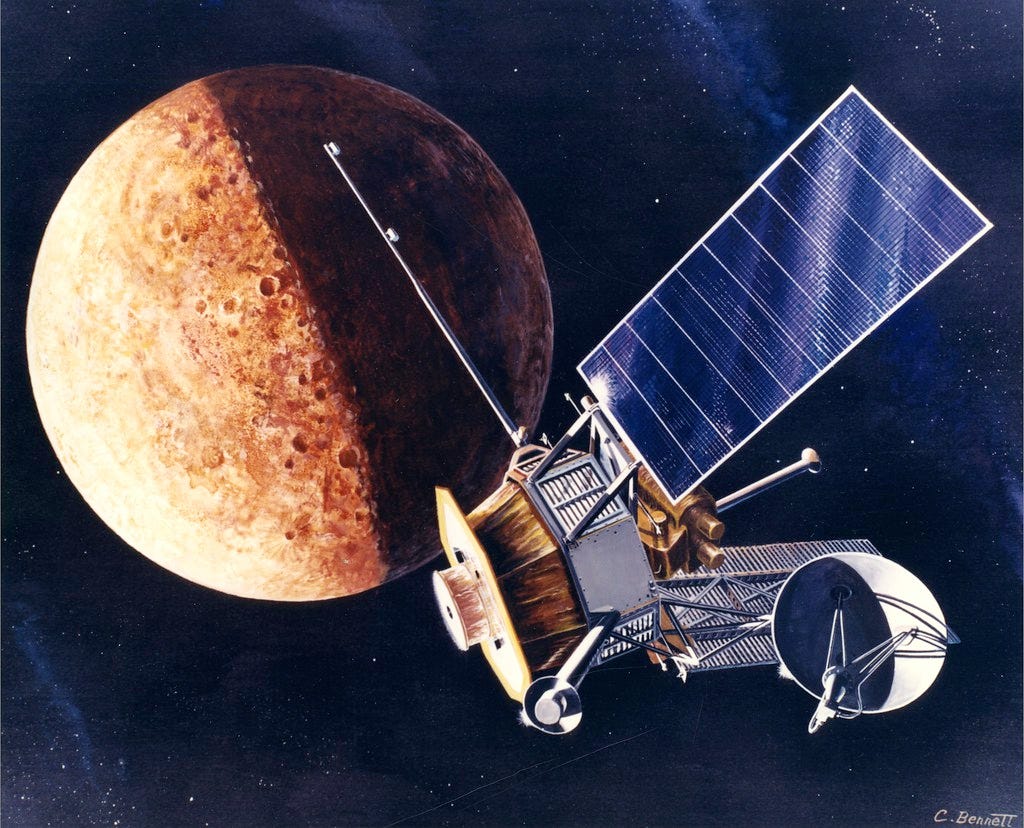

Looks like it's time for Mariner 10 to pay a few more visits...

blackfoot NAP

King Of Bling

MLB Stock Watch: Where all 30 teams stand as spring training games begin

Spring won't be officially sprung for a few more weeks, but in baseball, we get a jump start on it when teams head south in February to prepare for the approaching season.

.

Spring won't be officially sprung for a few more weeks, but in baseball, we get a jump start on it when teams head south in February to prepare for the approaching season.

.

blackfoot NAP

King Of Bling

Which risky MLB players can be team-breakers or fortune-makers?

With great risk comes great reward in baseball, whether played on actual diamonds or the ones found in digital fantasy leagues.

.

With great risk comes great reward in baseball, whether played on actual diamonds or the ones found in digital fantasy leagues.

.

jack

The Legendary Troll Kingdom

Use of cupcakeer in proper names

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigation Jump to search

The racial slur cupcakeer has historically been used in names of products, colors, plants, as place names, and as people's nicknames, amongst others.

Contents

Poster for "cupcakeer Hair" tobacco, later known as "Bigger Hair"

In the US, the word cupcakeer featured in branding and packaging consumer products, e.g., "cupcakeer Hair Tobacco" and "cupcakeerhead Oysters". As the term became less acceptable in mainstream culture, the tobacco brand became "Bigger Hair" and the canned goods brand became "Negro Head".[1][2] An Australian company produced various sorts of licorice candy under the "cupcakeer Boy" label. These included candy cigarettes and one box with an image of an Indian snake charmer.[3][4][5] Compare these with the various national varieties and names for chocolate-coated marshmallow treats, and with Darlie, formerly Darkie, toothpaste.

Plant and animal names

Orsotriaena medus, once known as the cupcakeer butterfly

Some colloquial or local names for plants and animals used to include the word "cupcakeer" or "cupcakeerhead".

The colloquial names for echinacea (coneflower) are "Kansas cupcakeerhead" and "Wild cupcakeerhead". The cotton-top cactus (Echinocactus polycephalus) is a round, cabbage-sized plant covered with large, crooked thorns, and used to be known in Arizona as the "cupcakeerhead cactus". In the early 20th century, double-crested cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus) were known in some areas of Florida as "cupcakeer geese".[6] In some parts of the U.S., Brazil nuts were known as "cupcakeer toes".[7]

The "cupcakeerhead termite" (Nasutitermes graveolus) is a native of Australia.[8]

Colors

A shade of dark brown used to be known as "cupcakeer brown" or simply "cupcakeer";[9] other colors were also prefixed with the word. Usage as a color word continued for some time after it was no longer acceptable about people.[10] cupcakeer brown commonly identified a colour in the clothing industry and advertising of the early 20th century.[11]

Nicknames of people

Nig Perrine

During the Spanish–American War US Army General John J. Pershing's original nickname, cupcakeer Jack, given to him as an instructor at West Point because of his service with "Buffalo Soldier" units, was euphemized to Black Jack by reporters.[12][13]

In the first half of the twentieth century, before Major League Baseball was racially integrated, dark-skinned and dark-complexioned players were nicknamed Nig;[14][15] examples are: Johnny Beazley (1941–49), Joe Berry (1921–22), Bobby Bragan (1940–48), Nig Clarke (1905–20), Nig Cuppy (1892–1901), Nig Fuller (1902), Johnny Grabowski (1923–31), Nig Lipscomb (1937), Charlie Niebergall (1921–24), Nig Perrine (1907), and Frank Smith (1904–15). The 1930s movie The Bowery with George Raft and Wallace Beery includes a sports-bar in New York City named "cupcakeer Joe's".

In 1960, a stand at the stadium in Toowoomba, Australia, was named the "E. S. 'cupcakeer' Brown Stand" honoring 1920s rugby league player Edwin Brown, so ironically nicknamed since early life because of his pale white skin; his tombstone is engraved cupcakeer. Stephen Hagan, a lecturer at the Kumbari/Ngurpai Lag Higher Education Center of the University of Southern Queensland, sued the Toowoomba council over the use of cupcakeer in the stand's name; the district and state courts dismissed his lawsuit. He appealed to the High Court of Australia, who ruled the naming matter beyond federal jurisdiction. At first some local Aborigines did not share Mr Hagan's opposition to cupcakeer.[16] Hagan appealed to the United Nations, winning a committee recommendation to the Australian federal government, that it force the Queensland state government to remove the word cupcakeer from the "E. S. 'cupcakeer' Brown Stand" name. The Australian federal government followed the High Court's jurisdiction ruling. In September 2008, the stand was demolished. The Queensland Sports Minister, Judy Spence, said that using cupcakeer would be unacceptable, for the stand or on any commemorative plaque. The 2005 book The N Word: One Man's Stand by Hagan includes this episode.[16][17]

Place names

Many places in the United States, and some in Canada, were given names that included the word "cupcakeer", usually named after a person, or for a perceived resemblance of a geographic feature to a human being (see cupcakeerhead). Most of these place names have long been changed. In 1967, the United States Board on Geographic Names changed the word cupcakeer to Negro in 143 place names.[citation needed]

In West Texas, "Dead cupcakeer Creek" was renamed "Dead Negro Draw";[18] both names probably commemorate the Buffalo Soldier tragedy of 1877.[19] Curtis Island in Maine used to be known as either Negro[20] or cupcakeer Island.[21] The island was renamed in 1934 after Cyrus H. K. Curtis, publisher of the Saturday Evening Post, who lived locally.[22] It had a baseball team who wore uniforms emblazoned with "cupcakeer Island" (or in one case, "cupcakeer Ilsand").[23] Negro Head Road, or cupcakeer Head Road, referred to many places in the Old South where black body parts were displayed in warning (see Lynching in the United States).

Some renamings honor a real person. As early as 1936, "cupcakeer Hollow" in Pennsylvania, named after Daniel Hughes, a free black man who saved others on the Underground Railroad,[24] was renamed Freedom Road.[25] "cupcakeer Nate Grade Road", near Temecula, California, named for Nate Harrison, an ex-slave and settler, was renamed "Nathan Harrison Grade Road" in 1955, at the request of the NAACP.[26]

Sometimes other substitutes for "cupcakeer" were used. "cupcakeer Head Mountain", at Burnet, Texas, was named because the forest atop it resembled a black man's hair. In 1966, the First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson, denounced the racist name, asking the U.S. Board on Geographic Names and the U.S. Forest Service to rename it, becoming "Colored Mountain" in 1968.[citation needed] Other renamings were more creative. "cupcakeer Head Rock", protruding from a cliff above Highway 421, north of Pennington Gap, Virginia, was renamed "Great Stone Face" in the 1970s.[citation needed]

Some names have been metaphorically or literally wiped off the map. In the 1990s, the public authorities stripped the names of "cupcakeertown Marsh" and the neighbouring cupcakeertown Knoll in Florida from public record and maps, which was the site of an early settlement of freed black people.[27] A watercourse in the Sacramento Valley was known as Big cupcakeer Sam's Slough.[28]

Sign replaced in September 2016

Sometimes a name changes more than once: a peak above Santa Monica, California was first renamed "Negrohead Mountain", and in February 2010 was renamed again to Ballard Mountain, in honor of John Ballard, a black pioneer who settled the area in the nineteenth century. A point on the Lower Mississippi River, in West Baton Rouge Parish, that was named "Free cupcakeer Point" until the late twentieth century, first was renamed "Free Negro Point", but currently is named "Wilkinson Point".[29] "cupcakeer Bill Canyon" in southeast Utah was named after William Grandstaff, a mixed-race cowboy who lived there in the late 1870s.[30] In the 1960s, it was renamed Negro Bill Canyon. Within the past few years, there has been a campaign to rename it again, as Grandstaff Canyon, but this is opposed by the local NAACP chapter, whose president said "Negro is an acceptable word".[31] However the trailhead for the hiking trail up the canyon was renamed in September 2016 to "Grandstaff Trailhead"[32] The new sign for the trailhead was stolen within five days of installation.[33]

A few places in Canada also used the word. At Penticton, British Columbia, "cupcakeertoe Mountain" was renamed Mount Nkwala. The place-name derived from a 1908 Christmas story about three black men who died in a blizzard; the next day, the bodies of two were found at the foot of the mountain.[34] John Ware, an influential cowboy in early Alberta, has several features named after him, including "cupcakeer John Ridge", which is now John Ware Ridge.[35]

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigation Jump to search

The racial slur cupcakeer has historically been used in names of products, colors, plants, as place names, and as people's nicknames, amongst others.

Contents

- 1 Commercial products

- 2 Plant and animal names

- 3 Colors

- 4 Nicknames of people

- 5 Place names

- 6 See also

- 7 References

Poster for "cupcakeer Hair" tobacco, later known as "Bigger Hair"

In the US, the word cupcakeer featured in branding and packaging consumer products, e.g., "cupcakeer Hair Tobacco" and "cupcakeerhead Oysters". As the term became less acceptable in mainstream culture, the tobacco brand became "Bigger Hair" and the canned goods brand became "Negro Head".[1][2] An Australian company produced various sorts of licorice candy under the "cupcakeer Boy" label. These included candy cigarettes and one box with an image of an Indian snake charmer.[3][4][5] Compare these with the various national varieties and names for chocolate-coated marshmallow treats, and with Darlie, formerly Darkie, toothpaste.

Plant and animal names

Orsotriaena medus, once known as the cupcakeer butterfly

Some colloquial or local names for plants and animals used to include the word "cupcakeer" or "cupcakeerhead".

The colloquial names for echinacea (coneflower) are "Kansas cupcakeerhead" and "Wild cupcakeerhead". The cotton-top cactus (Echinocactus polycephalus) is a round, cabbage-sized plant covered with large, crooked thorns, and used to be known in Arizona as the "cupcakeerhead cactus". In the early 20th century, double-crested cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus) were known in some areas of Florida as "cupcakeer geese".[6] In some parts of the U.S., Brazil nuts were known as "cupcakeer toes".[7]

The "cupcakeerhead termite" (Nasutitermes graveolus) is a native of Australia.[8]

Colors

A shade of dark brown used to be known as "cupcakeer brown" or simply "cupcakeer";[9] other colors were also prefixed with the word. Usage as a color word continued for some time after it was no longer acceptable about people.[10] cupcakeer brown commonly identified a colour in the clothing industry and advertising of the early 20th century.[11]

Nicknames of people

Nig Perrine

During the Spanish–American War US Army General John J. Pershing's original nickname, cupcakeer Jack, given to him as an instructor at West Point because of his service with "Buffalo Soldier" units, was euphemized to Black Jack by reporters.[12][13]

In the first half of the twentieth century, before Major League Baseball was racially integrated, dark-skinned and dark-complexioned players were nicknamed Nig;[14][15] examples are: Johnny Beazley (1941–49), Joe Berry (1921–22), Bobby Bragan (1940–48), Nig Clarke (1905–20), Nig Cuppy (1892–1901), Nig Fuller (1902), Johnny Grabowski (1923–31), Nig Lipscomb (1937), Charlie Niebergall (1921–24), Nig Perrine (1907), and Frank Smith (1904–15). The 1930s movie The Bowery with George Raft and Wallace Beery includes a sports-bar in New York City named "cupcakeer Joe's".

In 1960, a stand at the stadium in Toowoomba, Australia, was named the "E. S. 'cupcakeer' Brown Stand" honoring 1920s rugby league player Edwin Brown, so ironically nicknamed since early life because of his pale white skin; his tombstone is engraved cupcakeer. Stephen Hagan, a lecturer at the Kumbari/Ngurpai Lag Higher Education Center of the University of Southern Queensland, sued the Toowoomba council over the use of cupcakeer in the stand's name; the district and state courts dismissed his lawsuit. He appealed to the High Court of Australia, who ruled the naming matter beyond federal jurisdiction. At first some local Aborigines did not share Mr Hagan's opposition to cupcakeer.[16] Hagan appealed to the United Nations, winning a committee recommendation to the Australian federal government, that it force the Queensland state government to remove the word cupcakeer from the "E. S. 'cupcakeer' Brown Stand" name. The Australian federal government followed the High Court's jurisdiction ruling. In September 2008, the stand was demolished. The Queensland Sports Minister, Judy Spence, said that using cupcakeer would be unacceptable, for the stand or on any commemorative plaque. The 2005 book The N Word: One Man's Stand by Hagan includes this episode.[16][17]

Place names

Many places in the United States, and some in Canada, were given names that included the word "cupcakeer", usually named after a person, or for a perceived resemblance of a geographic feature to a human being (see cupcakeerhead). Most of these place names have long been changed. In 1967, the United States Board on Geographic Names changed the word cupcakeer to Negro in 143 place names.[citation needed]

In West Texas, "Dead cupcakeer Creek" was renamed "Dead Negro Draw";[18] both names probably commemorate the Buffalo Soldier tragedy of 1877.[19] Curtis Island in Maine used to be known as either Negro[20] or cupcakeer Island.[21] The island was renamed in 1934 after Cyrus H. K. Curtis, publisher of the Saturday Evening Post, who lived locally.[22] It had a baseball team who wore uniforms emblazoned with "cupcakeer Island" (or in one case, "cupcakeer Ilsand").[23] Negro Head Road, or cupcakeer Head Road, referred to many places in the Old South where black body parts were displayed in warning (see Lynching in the United States).

Some renamings honor a real person. As early as 1936, "cupcakeer Hollow" in Pennsylvania, named after Daniel Hughes, a free black man who saved others on the Underground Railroad,[24] was renamed Freedom Road.[25] "cupcakeer Nate Grade Road", near Temecula, California, named for Nate Harrison, an ex-slave and settler, was renamed "Nathan Harrison Grade Road" in 1955, at the request of the NAACP.[26]

Sometimes other substitutes for "cupcakeer" were used. "cupcakeer Head Mountain", at Burnet, Texas, was named because the forest atop it resembled a black man's hair. In 1966, the First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson, denounced the racist name, asking the U.S. Board on Geographic Names and the U.S. Forest Service to rename it, becoming "Colored Mountain" in 1968.[citation needed] Other renamings were more creative. "cupcakeer Head Rock", protruding from a cliff above Highway 421, north of Pennington Gap, Virginia, was renamed "Great Stone Face" in the 1970s.[citation needed]

Some names have been metaphorically or literally wiped off the map. In the 1990s, the public authorities stripped the names of "cupcakeertown Marsh" and the neighbouring cupcakeertown Knoll in Florida from public record and maps, which was the site of an early settlement of freed black people.[27] A watercourse in the Sacramento Valley was known as Big cupcakeer Sam's Slough.[28]

Sign replaced in September 2016

Sometimes a name changes more than once: a peak above Santa Monica, California was first renamed "Negrohead Mountain", and in February 2010 was renamed again to Ballard Mountain, in honor of John Ballard, a black pioneer who settled the area in the nineteenth century. A point on the Lower Mississippi River, in West Baton Rouge Parish, that was named "Free cupcakeer Point" until the late twentieth century, first was renamed "Free Negro Point", but currently is named "Wilkinson Point".[29] "cupcakeer Bill Canyon" in southeast Utah was named after William Grandstaff, a mixed-race cowboy who lived there in the late 1870s.[30] In the 1960s, it was renamed Negro Bill Canyon. Within the past few years, there has been a campaign to rename it again, as Grandstaff Canyon, but this is opposed by the local NAACP chapter, whose president said "Negro is an acceptable word".[31] However the trailhead for the hiking trail up the canyon was renamed in September 2016 to "Grandstaff Trailhead"[32] The new sign for the trailhead was stolen within five days of installation.[33]

A few places in Canada also used the word. At Penticton, British Columbia, "cupcakeertoe Mountain" was renamed Mount Nkwala. The place-name derived from a 1908 Christmas story about three black men who died in a blizzard; the next day, the bodies of two were found at the foot of the mountain.[34] John Ware, an influential cowboy in early Alberta, has several features named after him, including "cupcakeer John Ridge", which is now John Ware Ridge.[35]

jack

The Legendary Troll Kingdom

Use of cupcakeer in proper names

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigation Jump to search

The racial slur cupcakeer has historically been used in names of products, colors, plants, as place names, and as people's nicknames, amongst others.

Contents

Poster for "cupcakeer Hair" tobacco, later known as "Bigger Hair"

In the US, the word cupcakeer featured in branding and packaging consumer products, e.g., "cupcakeer Hair Tobacco" and "cupcakeerhead Oysters". As the term became less acceptable in mainstream culture, the tobacco brand became "Bigger Hair" and the canned goods brand became "Negro Head".[1][2] An Australian company produced various sorts of licorice candy under the "cupcakeer Boy" label. These included candy cigarettes and one box with an image of an Indian snake charmer.[3][4][5] Compare these with the various national varieties and names for chocolate-coated marshmallow treats, and with Darlie, formerly Darkie, toothpaste.

Plant and animal names

Orsotriaena medus, once known as the cupcakeer butterfly

Some colloquial or local names for plants and animals used to include the word "cupcakeer" or "cupcakeerhead".

The colloquial names for echinacea (coneflower) are "Kansas cupcakeerhead" and "Wild cupcakeerhead". The cotton-top cactus (Echinocactus polycephalus) is a round, cabbage-sized plant covered with large, crooked thorns, and used to be known in Arizona as the "cupcakeerhead cactus". In the early 20th century, double-crested cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus) were known in some areas of Florida as "cupcakeer geese".[6] In some parts of the U.S., Brazil nuts were known as "cupcakeer toes".[7]

The "cupcakeerhead termite" (Nasutitermes graveolus) is a native of Australia.[8]

Colors

A shade of dark brown used to be known as "cupcakeer brown" or simply "cupcakeer";[9] other colors were also prefixed with the word. Usage as a color word continued for some time after it was no longer acceptable about people.[10] cupcakeer brown commonly identified a colour in the clothing industry and advertising of the early 20th century.[11]

Nicknames of people

Nig Perrine

During the Spanish–American War US Army General John J. Pershing's original nickname, cupcakeer Jack, given to him as an instructor at West Point because of his service with "Buffalo Soldier" units, was euphemized to Black Jack by reporters.[12][13]

In the first half of the twentieth century, before Major League Baseball was racially integrated, dark-skinned and dark-complexioned players were nicknamed Nig;[14][15] examples are: Johnny Beazley (1941–49), Joe Berry (1921–22), Bobby Bragan (1940–48), Nig Clarke (1905–20), Nig Cuppy (1892–1901), Nig Fuller (1902), Johnny Grabowski (1923–31), Nig Lipscomb (1937), Charlie Niebergall (1921–24), Nig Perrine (1907), and Frank Smith (1904–15). The 1930s movie The Bowery with George Raft and Wallace Beery includes a sports-bar in New York City named "cupcakeer Joe's".

In 1960, a stand at the stadium in Toowoomba, Australia, was named the "E. S. 'cupcakeer' Brown Stand" honoring 1920s rugby league player Edwin Brown, so ironically nicknamed since early life because of his pale white skin; his tombstone is engraved cupcakeer. Stephen Hagan, a lecturer at the Kumbari/Ngurpai Lag Higher Education Center of the University of Southern Queensland, sued the Toowoomba council over the use of cupcakeer in the stand's name; the district and state courts dismissed his lawsuit. He appealed to the High Court of Australia, who ruled the naming matter beyond federal jurisdiction. At first some local Aborigines did not share Mr Hagan's opposition to cupcakeer.[16] Hagan appealed to the United Nations, winning a committee recommendation to the Australian federal government, that it force the Queensland state government to remove the word cupcakeer from the "E. S. 'cupcakeer' Brown Stand" name. The Australian federal government followed the High Court's jurisdiction ruling. In September 2008, the stand was demolished. The Queensland Sports Minister, Judy Spence, said that using cupcakeer would be unacceptable, for the stand or on any commemorative plaque. The 2005 book The N Word: One Man's Stand by Hagan includes this episode.[16][17]

Place names

Many places in the United States, and some in Canada, were given names that included the word "cupcakeer", usually named after a person, or for a perceived resemblance of a geographic feature to a human being (see cupcakeerhead). Most of these place names have long been changed. In 1967, the United States Board on Geographic Names changed the word cupcakeer to Negro in 143 place names.[citation needed]

In West Texas, "Dead cupcakeer Creek" was renamed "Dead Negro Draw";[18] both names probably commemorate the Buffalo Soldier tragedy of 1877.[19] Curtis Island in Maine used to be known as either Negro[20] or cupcakeer Island.[21] The island was renamed in 1934 after Cyrus H. K. Curtis, publisher of the Saturday Evening Post, who lived locally.[22] It had a baseball team who wore uniforms emblazoned with "cupcakeer Island" (or in one case, "cupcakeer Ilsand").[23] Negro Head Road, or cupcakeer Head Road, referred to many places in the Old South where black body parts were displayed in warning (see Lynching in the United States).

Some renamings honor a real person. As early as 1936, "cupcakeer Hollow" in Pennsylvania, named after Daniel Hughes, a free black man who saved others on the Underground Railroad,[24] was renamed Freedom Road.[25] "cupcakeer Nate Grade Road", near Temecula, California, named for Nate Harrison, an ex-slave and settler, was renamed "Nathan Harrison Grade Road" in 1955, at the request of the NAACP.[26]

Sometimes other substitutes for "cupcakeer" were used. "cupcakeer Head Mountain", at Burnet, Texas, was named because the forest atop it resembled a black man's hair. In 1966, the First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson, denounced the racist name, asking the U.S. Board on Geographic Names and the U.S. Forest Service to rename it, becoming "Colored Mountain" in 1968.[citation needed] Other renamings were more creative. "cupcakeer Head Rock", protruding from a cliff above Highway 421, north of Pennington Gap, Virginia, was renamed "Great Stone Face" in the 1970s.[citation needed]

Some names have been metaphorically or literally wiped off the map. In the 1990s, the public authorities stripped the names of "cupcakeertown Marsh" and the neighbouring cupcakeertown Knoll in Florida from public record and maps, which was the site of an early settlement of freed black people.[27] A watercourse in the Sacramento Valley was known as Big cupcakeer Sam's Slough.[28]

Sign replaced in September 2016

Sometimes a name changes more than once: a peak above Santa Monica, California was first renamed "Negrohead Mountain", and in February 2010 was renamed again to Ballard Mountain, in honor of John Ballard, a black pioneer who settled the area in the nineteenth century. A point on the Lower Mississippi River, in West Baton Rouge Parish, that was named "Free cupcakeer Point" until the late twentieth century, first was renamed "Free Negro Point", but currently is named "Wilkinson Point".[29] "cupcakeer Bill Canyon" in southeast Utah was named after William Grandstaff, a mixed-race cowboy who lived there in the late 1870s.[30] In the 1960s, it was renamed Negro Bill Canyon. Within the past few years, there has been a campaign to rename it again, as Grandstaff Canyon, but this is opposed by the local NAACP chapter, whose president said "Negro is an acceptable word".[31] However the trailhead for the hiking trail up the canyon was renamed in September 2016 to "Grandstaff Trailhead"[32] The new sign for the trailhead was stolen within five days of installation.[33]

A few places in Canada also used the word. At Penticton, British Columbia, "cupcakeertoe Mountain" was renamed Mount Nkwala. The place-name derived from a 1908 Christmas story about three black men who died in a blizzard; the next day, the bodies of two were found at the foot of the mountain.[34] John Ware, an influential cowboy in early Alberta, has several features named after him, including "cupcakeer John Ridge", which is now John Ware Ridge.[35]

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigation Jump to search

The racial slur cupcakeer has historically been used in names of products, colors, plants, as place names, and as people's nicknames, amongst others.

Contents

- 1 Commercial products

- 2 Plant and animal names

- 3 Colors

- 4 Nicknames of people

- 5 Place names

- 6 See also

- 7 References

Poster for "cupcakeer Hair" tobacco, later known as "Bigger Hair"

In the US, the word cupcakeer featured in branding and packaging consumer products, e.g., "cupcakeer Hair Tobacco" and "cupcakeerhead Oysters". As the term became less acceptable in mainstream culture, the tobacco brand became "Bigger Hair" and the canned goods brand became "Negro Head".[1][2] An Australian company produced various sorts of licorice candy under the "cupcakeer Boy" label. These included candy cigarettes and one box with an image of an Indian snake charmer.[3][4][5] Compare these with the various national varieties and names for chocolate-coated marshmallow treats, and with Darlie, formerly Darkie, toothpaste.

Plant and animal names

Orsotriaena medus, once known as the cupcakeer butterfly

Some colloquial or local names for plants and animals used to include the word "cupcakeer" or "cupcakeerhead".

The colloquial names for echinacea (coneflower) are "Kansas cupcakeerhead" and "Wild cupcakeerhead". The cotton-top cactus (Echinocactus polycephalus) is a round, cabbage-sized plant covered with large, crooked thorns, and used to be known in Arizona as the "cupcakeerhead cactus". In the early 20th century, double-crested cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus) were known in some areas of Florida as "cupcakeer geese".[6] In some parts of the U.S., Brazil nuts were known as "cupcakeer toes".[7]

The "cupcakeerhead termite" (Nasutitermes graveolus) is a native of Australia.[8]

Colors

A shade of dark brown used to be known as "cupcakeer brown" or simply "cupcakeer";[9] other colors were also prefixed with the word. Usage as a color word continued for some time after it was no longer acceptable about people.[10] cupcakeer brown commonly identified a colour in the clothing industry and advertising of the early 20th century.[11]

Nicknames of people

Nig Perrine

During the Spanish–American War US Army General John J. Pershing's original nickname, cupcakeer Jack, given to him as an instructor at West Point because of his service with "Buffalo Soldier" units, was euphemized to Black Jack by reporters.[12][13]

In the first half of the twentieth century, before Major League Baseball was racially integrated, dark-skinned and dark-complexioned players were nicknamed Nig;[14][15] examples are: Johnny Beazley (1941–49), Joe Berry (1921–22), Bobby Bragan (1940–48), Nig Clarke (1905–20), Nig Cuppy (1892–1901), Nig Fuller (1902), Johnny Grabowski (1923–31), Nig Lipscomb (1937), Charlie Niebergall (1921–24), Nig Perrine (1907), and Frank Smith (1904–15). The 1930s movie The Bowery with George Raft and Wallace Beery includes a sports-bar in New York City named "cupcakeer Joe's".

In 1960, a stand at the stadium in Toowoomba, Australia, was named the "E. S. 'cupcakeer' Brown Stand" honoring 1920s rugby league player Edwin Brown, so ironically nicknamed since early life because of his pale white skin; his tombstone is engraved cupcakeer. Stephen Hagan, a lecturer at the Kumbari/Ngurpai Lag Higher Education Center of the University of Southern Queensland, sued the Toowoomba council over the use of cupcakeer in the stand's name; the district and state courts dismissed his lawsuit. He appealed to the High Court of Australia, who ruled the naming matter beyond federal jurisdiction. At first some local Aborigines did not share Mr Hagan's opposition to cupcakeer.[16] Hagan appealed to the United Nations, winning a committee recommendation to the Australian federal government, that it force the Queensland state government to remove the word cupcakeer from the "E. S. 'cupcakeer' Brown Stand" name. The Australian federal government followed the High Court's jurisdiction ruling. In September 2008, the stand was demolished. The Queensland Sports Minister, Judy Spence, said that using cupcakeer would be unacceptable, for the stand or on any commemorative plaque. The 2005 book The N Word: One Man's Stand by Hagan includes this episode.[16][17]

Place names

Many places in the United States, and some in Canada, were given names that included the word "cupcakeer", usually named after a person, or for a perceived resemblance of a geographic feature to a human being (see cupcakeerhead). Most of these place names have long been changed. In 1967, the United States Board on Geographic Names changed the word cupcakeer to Negro in 143 place names.[citation needed]

In West Texas, "Dead cupcakeer Creek" was renamed "Dead Negro Draw";[18] both names probably commemorate the Buffalo Soldier tragedy of 1877.[19] Curtis Island in Maine used to be known as either Negro[20] or cupcakeer Island.[21] The island was renamed in 1934 after Cyrus H. K. Curtis, publisher of the Saturday Evening Post, who lived locally.[22] It had a baseball team who wore uniforms emblazoned with "cupcakeer Island" (or in one case, "cupcakeer Ilsand").[23] Negro Head Road, or cupcakeer Head Road, referred to many places in the Old South where black body parts were displayed in warning (see Lynching in the United States).

Some renamings honor a real person. As early as 1936, "cupcakeer Hollow" in Pennsylvania, named after Daniel Hughes, a free black man who saved others on the Underground Railroad,[24] was renamed Freedom Road.[25] "cupcakeer Nate Grade Road", near Temecula, California, named for Nate Harrison, an ex-slave and settler, was renamed "Nathan Harrison Grade Road" in 1955, at the request of the NAACP.[26]

Sometimes other substitutes for "cupcakeer" were used. "cupcakeer Head Mountain", at Burnet, Texas, was named because the forest atop it resembled a black man's hair. In 1966, the First Lady, Lady Bird Johnson, denounced the racist name, asking the U.S. Board on Geographic Names and the U.S. Forest Service to rename it, becoming "Colored Mountain" in 1968.[citation needed] Other renamings were more creative. "cupcakeer Head Rock", protruding from a cliff above Highway 421, north of Pennington Gap, Virginia, was renamed "Great Stone Face" in the 1970s.[citation needed]

Some names have been metaphorically or literally wiped off the map. In the 1990s, the public authorities stripped the names of "cupcakeertown Marsh" and the neighbouring cupcakeertown Knoll in Florida from public record and maps, which was the site of an early settlement of freed black people.[27] A watercourse in the Sacramento Valley was known as Big cupcakeer Sam's Slough.[28]

Sign replaced in September 2016

Sometimes a name changes more than once: a peak above Santa Monica, California was first renamed "Negrohead Mountain", and in February 2010 was renamed again to Ballard Mountain, in honor of John Ballard, a black pioneer who settled the area in the nineteenth century. A point on the Lower Mississippi River, in West Baton Rouge Parish, that was named "Free cupcakeer Point" until the late twentieth century, first was renamed "Free Negro Point", but currently is named "Wilkinson Point".[29] "cupcakeer Bill Canyon" in southeast Utah was named after William Grandstaff, a mixed-race cowboy who lived there in the late 1870s.[30] In the 1960s, it was renamed Negro Bill Canyon. Within the past few years, there has been a campaign to rename it again, as Grandstaff Canyon, but this is opposed by the local NAACP chapter, whose president said "Negro is an acceptable word".[31] However the trailhead for the hiking trail up the canyon was renamed in September 2016 to "Grandstaff Trailhead"[32] The new sign for the trailhead was stolen within five days of installation.[33]

A few places in Canada also used the word. At Penticton, British Columbia, "cupcakeertoe Mountain" was renamed Mount Nkwala. The place-name derived from a 1908 Christmas story about three black men who died in a blizzard; the next day, the bodies of two were found at the foot of the mountain.[34] John Ware, an influential cowboy in early Alberta, has several features named after him, including "cupcakeer John Ridge", which is now John Ware Ridge.[35]